本文來自

NYTimes

Architect Without Limits

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

Published: May 14, 2009

Frank Lloyd Wright died half a century ago, but people are still fighting over him.

The extraordinary scope of his genius, which touched on every aspect of American life, makes him one of the most daunting figures of the 20th century. But to many he is still the vain, megalomaniacal architect, someone who trampled over his clients' wishes, drained their bank accounts and left them with leaky roofs.

So 「Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward,」 which opens on Friday at the Guggenheim Museum, will be a disappointment to some. The show offers no new insight into his life's work. Nor is there any real sense of what makes him so controversial. It's a chaste show, as if the Guggenheim, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary, was determined to make Wright fit for civilized company.

The advantage of this low-key approach is that it puts the emphasis back where it belongs: on the work. There are more than 200 drawings, many never exhibited publicly before. More than a dozen scale models, some commissioned for the show, give a strong sense of the lucidity of his designs and the intimate relationship between building and landscape that was such a central theme of his art.

Taken as a whole, the exhibition conveys not only the remarkable scope of his interests, which ranged from affordable housing to reimagining the American city, but also the astonishing cohesiveness of that vision

— an achievement that has been matched by only one or two other architects in the 20th century.

One way to experience the show is as a straightforward tour of Wright's masterpieces. Organized by Thomas Krens and David van der Leer, it is arranged in roughly chronological order, so that you can spiral up through the highlights of his career: the reinvention of the suburban home and the office block, the obsession with car culture, the increasingly outlandish urban projects.

There is a stunning plaster model of the vaultlike interior of Unity Temple, built in Oak Park between 1905 and 1908. Just a bit farther up the ramp, another model painstakingly recreates the Great Workroom of the Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, Wis., with its delicate grid of mushroom columns and milky glass ceiling.

Such tightly composed, inward-looking structures contrast with the free-flowing spaces that we tend to associate with Wright's fantasy of a democratic, agrarian society.

But as always with Wright, the complexity of his approach reveals itself only after you begin to fit the pieces together. For Wright, the singular masterpiece was never enough. His aim was to create a framework for an entire new way of life, one that completely redefined the relationships between individual, family and community. And he pursued it with missionary zeal.

Wright went to extreme lengths to sell his dream of affordable housing for the masses, tirelessly promoting it in magazines.

The second-floor annex shows a small sampling of its various incarnations, including an elaborate model of the Jacobs House (1936-37), its walls and floors pulled apart and suspended from the ceiling on a system of wires and lead weights. One of Wright's earliest Usonian houses, the one-story Jacobs structure in Madison, Wis., was made of modest wood and brick and organized around a central hearth. Its L-shape layout framed a rectangular lawn, locking it into the landscape, so that the homeowner remained in close touch with the earth.

The ideas Wright explored in such projects were eventually woven into grander urban fantasies, first proposed in Broadacre City and later in The Living City project. In both, Usonian communities were dispersed over an endless matrix of highways and farmland, punctuated by the occasional residential tower.

The subtext of these plans, of course, was Wright's war with the city. To Wright, the congested neighborhoods of the traditional city were anathema to the spirit of unbridled individual freedom. His alternative, shaped by the car, represented a landscape of endless horizons. Sadly, it was also a model for suburban sprawl.

Wright continued to explore these themes until the end of his life, even as his formal language evolved. A model of the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium captures his growing obsession with the ziggurat and the spiral. A tourist destination that was planned for Sugarloaf Mountain, Md., but never built, the massive concrete structure coiled around a vast planetarium. The project combines his love of cars and his fascination with primitive forms, as if he were striving to weave together the whole continuum of human history.

In his 1957 Plan for Greater Baghdad, Wright went a step further, adapting his ideas to the heart of the ancient city. The plan is centered on a spectacular opera house enclosed beneath a spiraling dome and crowned by a statue of Alladin. Set on an island in the Tigris, the opera house was to be surrounded by tiers of parking and public gardens. A network of roadways extends like tendrils from this base, weaving along the edge of the river and tying the complex to the old city.

Just across the river, another ring of parking, almost a mile in diameter, encloses a new campus for Baghdad University.

Wright's fanciful design was never built, but it demonstrates the degree to which he remained distrustful of urban centers. Stubborn to the end, he saw the car as the city's salvation rather than its ruin. The cosmopolitan ideal is supplanted by a sprawling suburbia shaded by palms and date trees.

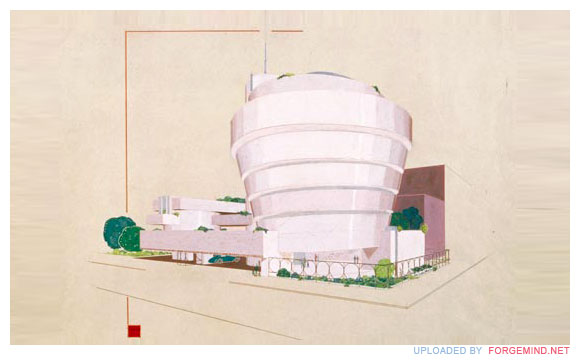

And what of the Guggenheim? Some will continue to see it as an example of Wright's brazen indifference to the city's history. With its aloof attitude toward the Manhattan street grid, the building still pushes buttons.

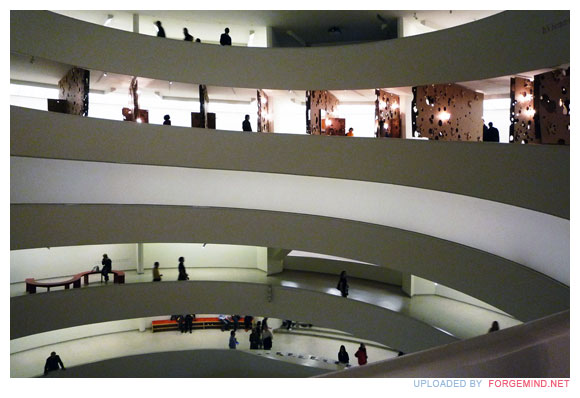

For his part, Wright saw the spiral as a symbol of life and rebirth. The reflecting pool at the bottom of his rotunda represented a seed, part of his vision of an organic architecture that sprouts directly from the earth.

Yet Wright also needed the city to make his vision work. The force of the spiral's upward thrust gains immeasurably from the grid that presses in on all sides. The ramps, too, can be read as an extension of the street life outside. Coiled tightly around the audience, they replicate the atmosphere of urban intensity that Wright supposedly so abhorred.

Or maybe not. In preparing for the show, the Guggenheim's curators decided to remove the frosting from a window at the lobby's southwest corner. The window frames a vista over a low retaining wall toward the corner of 88th Street and Fifth Avenue, where you can see people milling around the exterior of the building. It is the only real view out of the lobby, and it visually locks the building into the streetscape, making the city part of the composition.

I choose to see it as a gesture of love, of a sort, between Wright and the city he claimed to hate.